Lawrence Kincheloe has been a crucial participant in multiple Public Invention projects, ranging from the General Purpose Alarm Device (GPAD) and the NASA-MCOG to a new preliminary project, the Biochar Toilet. A proud Oklahoma resident, Kincheloe has been a part of his local open source community since graduating from university in 2009, and he has become prevalent in the wider movement since the Covid-19 pandemic. In a recent interview, he described the development of the open source movement in Oklahoma, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the promotion of open source hardware, and his inventor philosophy.

Lawrence Kincheloe: From University to Open Source Leader

Kincheloe studied computer science in college, where he was a part of the robotics club and participated in regular hackathons. However, after graduation, he noticed a comparative lack of community around technology. His search for a community with shared interests eventually carried him to the open source movement.

“There was a gap in post college community organizations,” Kincheloe said. “I was hungry for that, because I had that in college, and I didn’t have that after college. So, I found a couple of groups that did something similar.”

With this motivation, Kincheloe joined forces with a college friend, Joshua Gay, and began hosting hackathons and other events that supported conversations about technology and innovation. On the side, Kincheloe also began experimenting with open hardware and documented his work in a Wiki to share with others. This initial interest and involvement would lead him to engage with multiple open source initiatives, and embark on a journey of leadership and creation.

Oklahoma Open Source Initiatives

Kincheloe joined an early version of Factor E Farm, an open source ecology group that experiments with technology creation using only natural and local resources. Through partnership with this group, Kincheloe created a CNC plasma table that cut sheet metal. Make Magazine published an article about the project in January, 2010. Armed with this success, Kincheloe remained focused on hardware with his future projects.

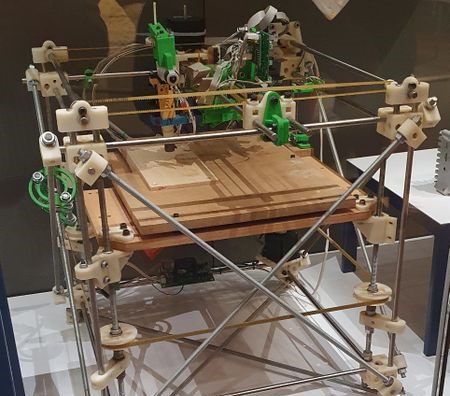

He also became a part of the RepRap Project, a project which kicked off wider interest in open source engineering and hardware. The project aimed to create a self-replicating 3D printer that could print other objects as well as additional versions of itself. Kincheloe reflected on this project and the burst of collaboration that it fostered.

“Anybody could do anything, and it was new,” he said. “Everyone was talking about it on the forums. The RepRap project movement had this glorious, early 2000s style where everyone was contributing.”

During the early 2000s era of open source, Makerspaces also spread throughout the United States. These spaces provided tools and technology that engineers and other creators could use freely. When a Makerspace appeared in Kincheloe’s local community in Oklahoma, he connected with its mission and got involved, supporting local creators and further building an innovative community.

“A Makerspace started in Oklahoma,” Kincheloe remembered. “That was, I guess, my first, and I was really interested in being a part of that. Then that became my main drive for creating community spaces and community organization. I think that lasted two or three years, and it eventually closed.”

Open Source Hardware and the OKC User Group

“I decided that what I really wanted to focus on was creating an electronics user group. So, I created the Oklahoma City, or Oklahoma, Open Source Hardware User Group.” – Lawrence Kincheloe

Kincheloe remained involved in creating multiple Makerspaces, but was struck with the difficulty of keeping them open for long periods of time. This prompted him to create his own organization which would continue to promote hardware creation, but would have more structured support than a Makerspace.

“Running a nonprofit is very difficult,” he shared. “But from that space, more Makerspaces sprung up. I participated in those, but at some point I got tired of having spaces form and collapse, and form and collapse. I decided that what I really wanted to focus on was creating an electronics user group. So, I created the Oklahoma City, or Oklahoma, Open Source Hardware User Group.”

The OKC User Group is still active today, with over 1,200 members. They continue to meet in-person to pursue technical innovation as its own end. The group has become a major part of the Techlahoma organization, which supports tech enthusiasts in the state with events, networking opportunities, funding, and most of all, a like-minded community.

For Kincheloe, this community aspect was more crucial than anything else due to the general lack of support for open hardware at the time. While open software had found its enthusiasts due to ease of access and iteration, hardware had more difficulty getting off the ground. The unavoidable costs of prototypes, the necessary gear to create iterations, and the increased cost of testing all raised barriers to entry for hardware project teams. However, Kincheloe was determined to promote this niche in the open source movement.

“There was nobody else who cared about open source hardware like I did,” Kincheloe said. “[But] I was going to put my little flag in the sand, and be like, ‘This is my user group. It’s about open source hardware. We’re gonna talk about open source hardware. If anyone is going to hang out and talk about open source hardware, we’re going to do it.’ So, I started that up.”

The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Open Source Response

“The pandemic showed everyone that, yes, you can work remotely, and while having hubs of activity is important for a lot of reasons, it’s not the most important thing for doing good work.” – Lawrence Kincheloe

In the midst of this flush of activity in the early open source landscape, the rise and fall of Makerspaces, and the promotion of technology-related events and meetups, the Covid-19 pandemic hit. This global event forced the community to evolve. In-person events were cancelled, and many nonprofits struggled to retain membership. However, rather than weakening open source engineering, the global pandemic instead prompted a rapid response that continues to impact the fields of personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical technology.

“The pandemic changed everything for everyone,” Kincheloe said. “We went totally virtual with Open Source Hardware. The conversation started between people who were wanting to 3D print PPE, and people that were in the medical field trying to organize PPE manufacturing. I felt that was an important thing, because people were passionate about wanting to do something. And through that, people wanted to do things and create things.”

Thus, the pandemic pushed engineers and technologists towards open source engineering rather than away from it. Since then, the movement has shifted to include a more global collaborative environment, utilizing the remote work technology that grew popular during the pandemic. This melded well with open source’s emphasis on collaboration and the free sharing of ideas, and Kincheloe expanded on its impact and benefits.

“Everybody started working remote, and working remotely allowed everyone to work outside of their small geographical regions,” Kincheloe said. “The ability to work with somebody from New York, California, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Austin, and Denver, Colorado: it’s amazing. And the pandemic showed everyone that, yes, you can work remotely, and while having hubs of activity is important for a lot of reasons, it’s not the most important thing for doing good work.”

What it Means to be an Open Source Inventor

“Inventing is not really being the first one to think of something for the first time ever. It’s more about being the person to find an idea that fits the time and place.” – Lawrence Kincheloe

More recently, Kincheloe has contributed to multiple Public Invention projects, including its first alarm project the GPAD, the NASA Oxygen Concentrator, and the new Biochar Toilet initiative. Looking forward, he hopes to begin work on a biological computer project related to AI development. From 3D and PCB design to prototype fabrication, his contributions to the organization as an engineer and Invention Coach, have been crucial.

As an individual dedicated to the free sharing of innovative ideas and the technology community, Kincheloe shared what being an Inventor meant to him.

“I have an unconventional opinion that there really is no such thing as a sole inventor, and that really, what it is, is the person who gets celebrated for discovering the idea at the right time in the [right] place. But I think we should really think of invention as not a solo pursuit,” Kincheloe said, “because I think that, one, [it is] more healthy, and two, I think it’s more true. It also encourages everyone to be an inventor, and that inventing is not really being the first one to think of something for the first time ever. It’s more about being the person to find an idea that fits the time and place.”

In conclusion, the open source movement has proved to be resilient and dynamic, growing from the grassroots initiatives of the early 2000s to the vibrant community it is today. Kincheloe’s experience with this evolving field shows that, centrally, open source is about more than just finished projects and published papers. It is also about community, humility, and bettering society through innovation. Whether through membership in an official organization or contributions to project GitHubs and Wikis, the open source movement welcomes everyone of all skill sets to innovate and help build a better world.